Martin Ødegaard: Arsenal's #6, #8 and #10?

A new role for the Arsenal captain and some new fluidity for Arsenal

For plenty of personal reasons, it is far, far too long since my last newsletter. So I’m making my comeback with something some may consider far, far too long.

Apparently this post is too long for emails, with the images and gifs. I guess if you’re in your emails and you can’t see everything, it might just be safer to find and read it here.

Anyway, onto the serious stuff …

What does a central midfielder actually do? Hard question, isn’t it? They do loads of things, depending on who they are, who they play for, and where in midfield they play. Let’s make it a bit easier: midfielders in can broadly be categorised by where on the pitch they do their jobs. In front of their defence, behind their striker, or somewhere in between. Most midfielders are one or two of these things — you get box-to-box players who start from deep, nowadays you get a lot of creative ‘numbers 10s’ who play as number eights. And then there are very few players who can pop up and excel everywhere.

Steven Gerrard excelled in all three broad midfield categories during his career, first as a box-to-box player, then a second striker, and lastly a deep-lying playmaker. Jude Bellingham wears the number 22 (well, not for Real Madrid) because he strives to marry the defensive ability of a number four (or six), the box-to-box energy of a number eight and the creativity of a number 10. He comes pretty close to perfection but has definitely leaned more into the final third this season at Real Madrid to help his output explode, compared to his form as a true ‘22’ at Borussia Dortmund.

Xavi, perhaps the greatest midfielder of all time, comes to mind as another who — while a ball-dominant playmaker — had an influence over the entire field, from box-to-box. At his peak he enjoyed a 14-goal season with Barcelona but that was one of just two campaigns that saw him reach double figures. Arsenal fans will remember Cesc Fàbregas excelling often as a one-man midfield from 2007-10, doing it all.

But you maybe have to go all the way back to Alfredi Di Stéfano for the best example. I can’t claim to be any kind of authority on how good Di Stéfano truly was or how he played, but the superb @SergiXaviniesta on Twitter, the brilliant mind behind footballarguments — a project to watch and analyse basically every recording of the game that exists — can, and he says this:

Alfredo Di Stéfano fascinates me. Of all the historic players I have watched over the last couple of years his playing style is both the most old-fashioned and, in a way, the most modern. Post-modern even. Because in some ways football evolution hasn’t caught up yet with Di Stéfano – more than 50 years after he retired.

And this (slightly edited, read the whole thing here):

Alfredo Di Stéfano was the total footballer. No other player in the history of the game can claim to be as polyvalent as he was. … if you look it up, you will read that he was a centre forward and just maybe you will find the description “false nine” floating around somewhere. While none of that is entirely false, here is something that is much closer to the truth: Di Stéfano had no real position. At least not in any classical sense of the word.

Watch the earliest matches of him that have survived until today, especially the 1960 European Cup final, and you see a player who pops up everywhere across the field … Cruyff, at his very best, did so as well … the Real Madrid legend had both the skills and the work-rate to really become the complete footballer. Between libero and centre forward he could play every position. He even was a more than decent wide player. As far as I know, this is unmatched in football history. No player did as many things as well as Di Stéfano.

And if you want even more, here’s where @SergiXaviniesta ranks Di Stéfano alongside the other three (in his view, and his view really is more qualified than basically anyone else you’ll ever find) greatest of all time.

Anyway, let’s chat about how amazing Martin Ødegaard is.

Declan Rice has been signed to play most of his minutes at the base of the Arsenal midfield. Which is great, because he is brilliant. He is world class defensively and he is very good on the ball … but he is not a massive, massive volume passer. At least not yet. Compared to Thomas Partey and Jorginho, who have occupied the role when Rice hasn’t since the start of last season, Rice passes less often and his passing is a bit less progressive. Interestingly, he also likes to drift and pick up the ball on the left of the pitch, as he has also shown for West Ham and for England, whereas Partey and Jorginho favour the right-hand side. And that means a significant shift for the makeup of the Arsenal midfield.

With Partey or Jorginho playing last season, there was space to their left for Oleksandr Zinchenko and Granit Xhaka to fill the rest of the midfield.

But Rice liked to be in those spaces and Arsenal have signed Kai Havertz, who is excellently suited to push on from midfield and become an extra forward. But all that leaves a gap to Rice’s right that is not as naturally filled by Takehiro Tomiyasu and Ben White compared to Zinchenko on the left.

Step forward (or, rather, drift backward) Martin Ødegaard.

You get the idea.

Arsenal finished second last season for their highest finish since 2016 and picked up 84 points, their highest since 2004. But Mikel Arteta would have wanted the team to evolve — if you stand still, you’ll get overtaken — to remain unpredictable and the arrival of Rice not only improved the level in midfield but has opened up an opportunity to evolve the way Arsenal play.

In Arsenal’s first games of the season, Rice had support in midfield from Thomas Partey. Then, for four games, he didn’t. In the fourth of those we saw the new Ødegaard in his new role for maybe the first time, against Bournemouth.

That dynamic lasted one game before Jorginho was introduced to the side and then Ødegaard was sidelined by injury, and the Rice-Ødegaard midfield pairing has only reemerged over the course of the last week or so. Looking back to that Bournemouth game, though, it was stark how much space Arsenal created between the opposition midfield and backline when playing out from the back, essentially creating artificial counter-attacks, and Ødegaard was key with his technical ability but more importantly just his positioning, pulling Bournemouth number four Lewis Cook further upfield over and over again.

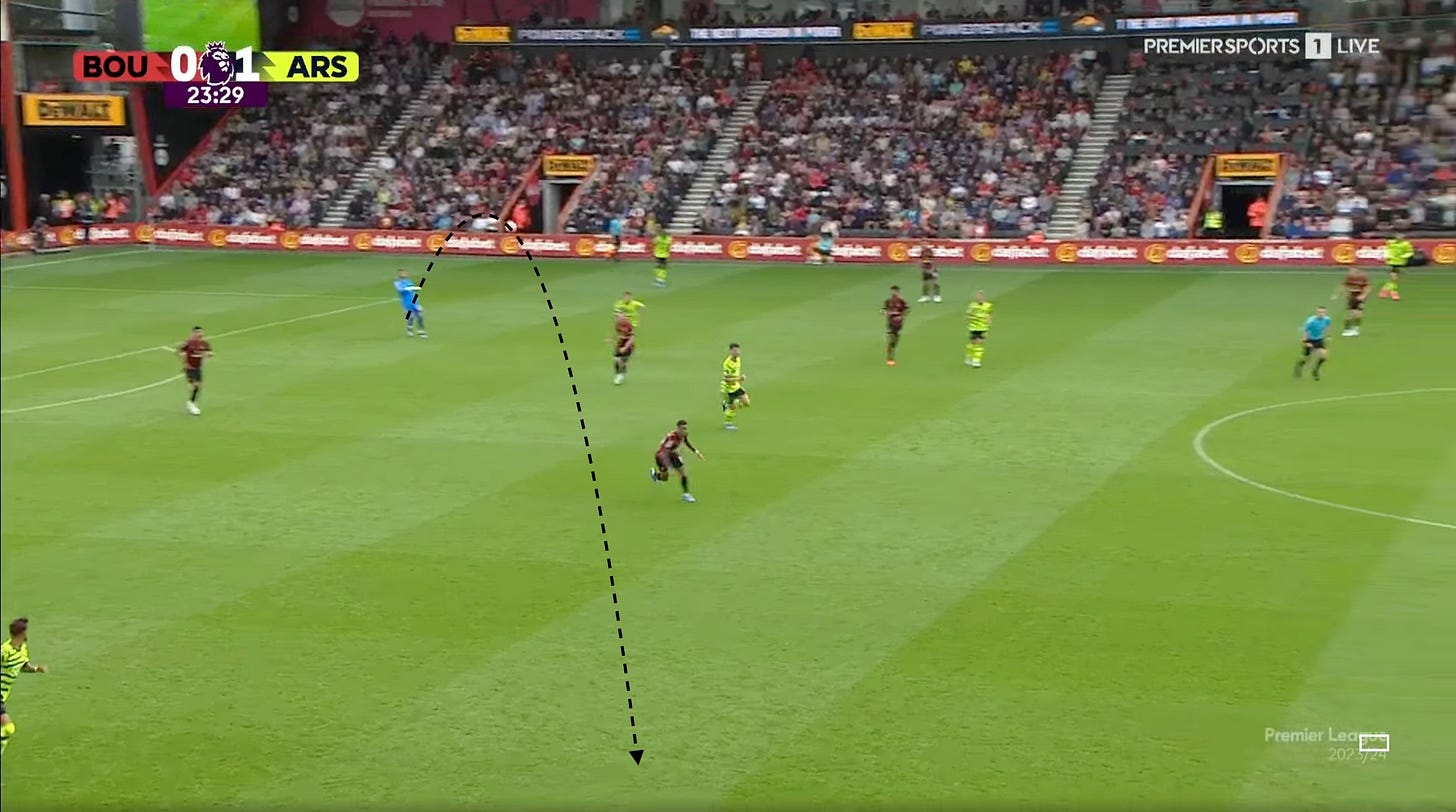

We saw it very early on in that game, with Ødegaard dropping deep, attracting Cook, and then Arsenal racing at the Bournemouth backline as it they approached the halfway line.

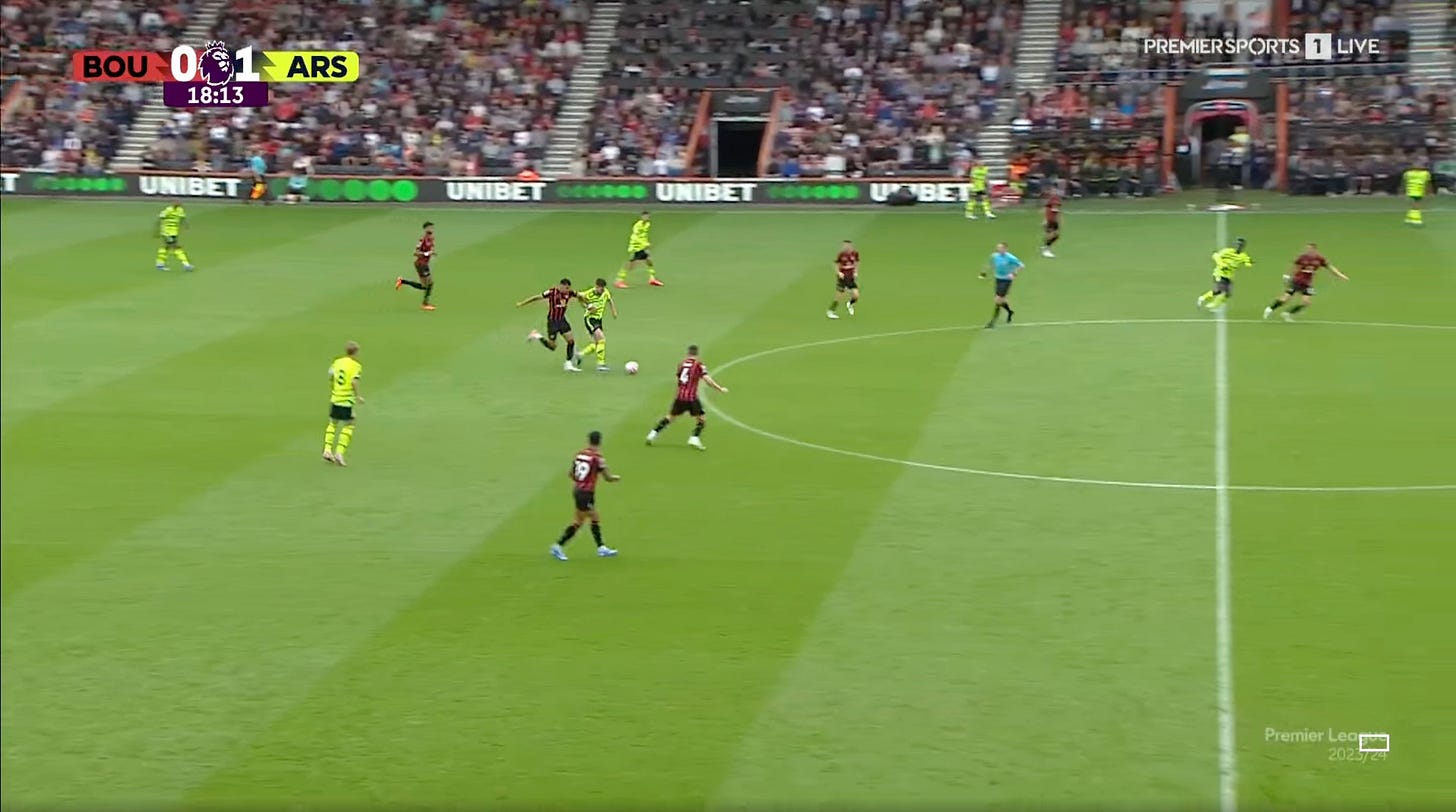

Ødegaard doesn’t stop at attracting pressure, though, he’s keen to join the attack too …

Really keen …

And he was keen to drop deep not to pick up the ball, just to create space for someone to pass elsewhere.

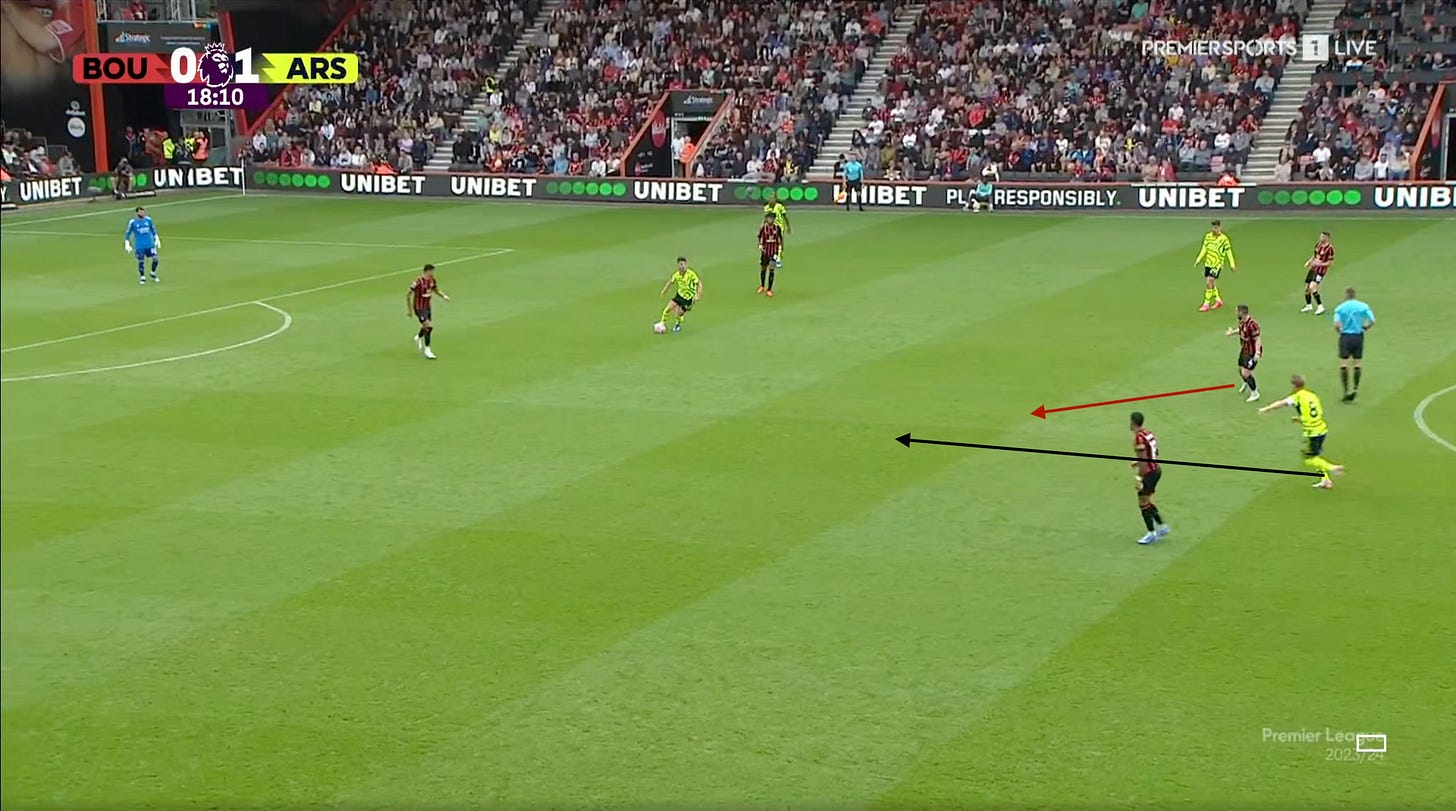

And he was also happy to attract players and opening spaces by moving backwards and Rice moved forwards with possession. Driving into space is one of the abilities that Rice has that made him worth every single penny of the record transfer fee Arsenal parted with him in the summer, having players who create opportunities for him to use that ability is essential.

Arsenal won 4-0 at Bournemouth — Ødegaard went from popping up deeper than usual to creating the opener and winning a penalty at the other end of the pitch — and then, annoyingly, we had to wait another six Premier League games before seeing the Arsenal captain in this role again.

Some headline figures to get you in the mood … against Wolves, Martin Ødegaard registered (in Premier League games since the start of last season):

His most passes (attempted - 95 and completed - 82)

His most progressive passes (21)

His second most carries (74)

His most through balls (3)

The second highest proportion of completed passes being 15+ yards (51.9%)

His highest progressive passing distance (507m, compared to a previous high of 398m)

His most middle third touches (39)

His third most passes into the final third (9 — most this season and only behind Fulham and Southampton last season, games where Arsenal were chasing goals for long spells)

As a quick addition, I don’t have anything here from the Luton game this midweek but that saw him register his joint most defensive third touches (14) and third highest progressive passing distance in any Premier League game since last season. That game also brought Ødegaard’s second most passes into the final third for a game this season, behind Wolves.

So, we have a different Martin Ødegaard now. He comes really deep to get the ball at times.

And he does more than ever in helping Arsenal get the ball upfield. The numbers bear that out when he’s on the ball but watch the games and you see how it’s the case when he isn’t as well.

One possible criticism of Arsenal last season is the rigidity in the team. Familiar patterns help players understand their jobs and they can be hard to stop. But executed imperfectly and you have issues and even executed well you’re predictable. Sometimes you just need your best players to move around, in turn they’ll move the opposition around, and solutions appear.

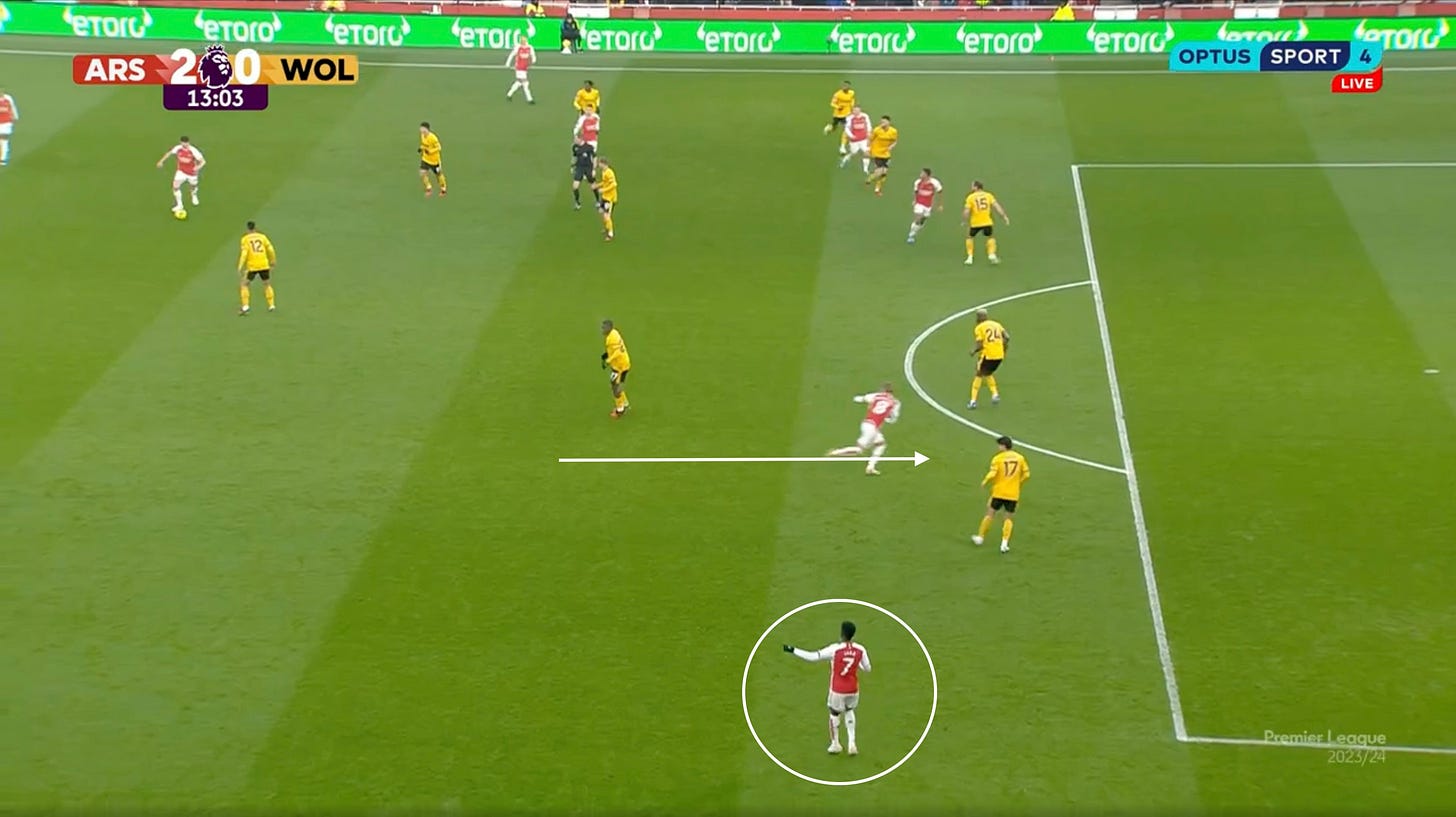

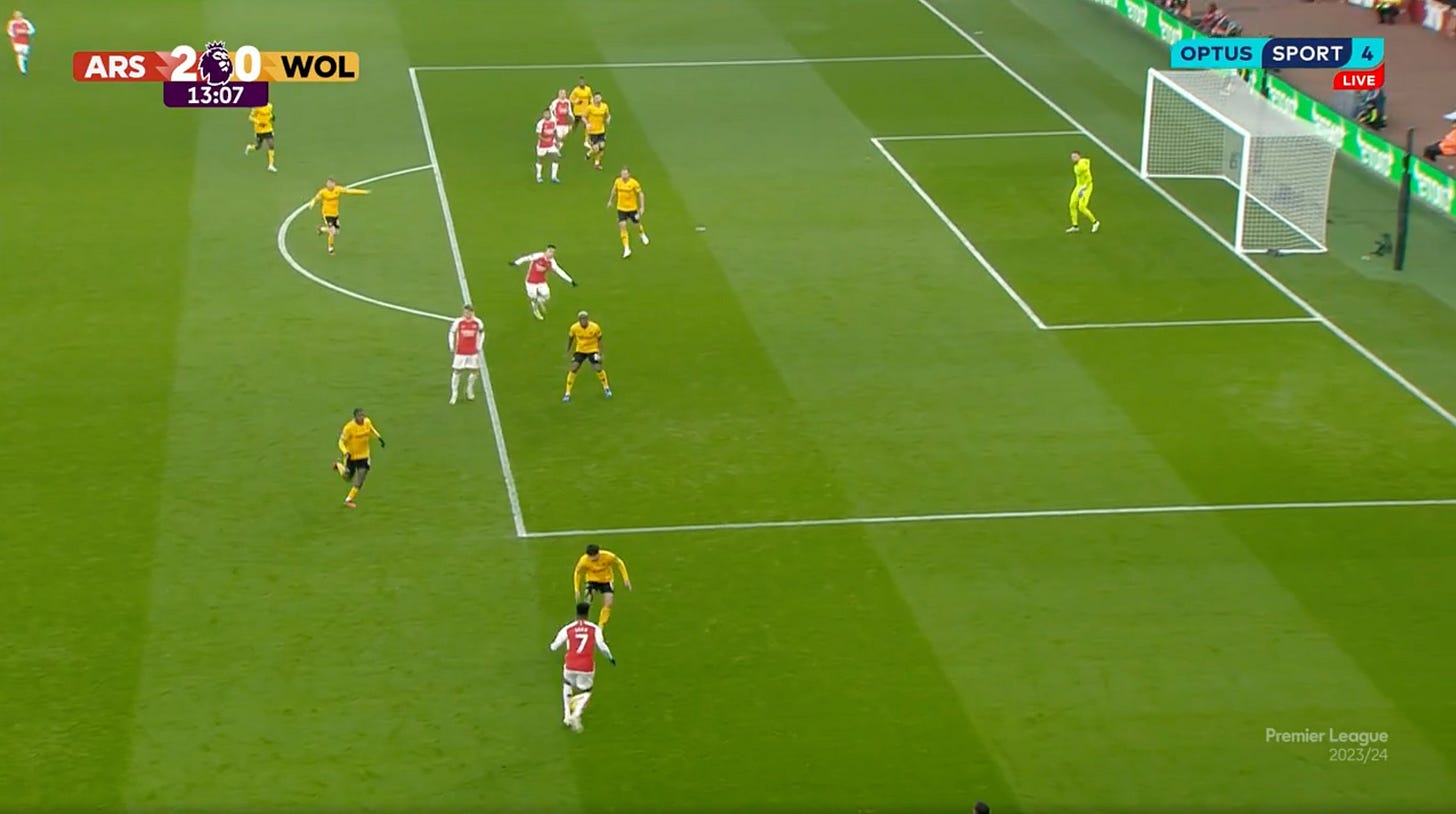

Here, Arsenal seem to be in a pretty standard 4-3-3 shape, everyone where you’d expect.

But Ødegaard drops back and across the pitch. After 10 seconds, William Saliba is still patiently waiting to play a pass and Arsenal are pulling Wolves around. Ødegaard’s marker in midfield doesn’t follow him, unwilling to be dragged out of position and occupied with Rice drifting to his side, so Hwang Hee-chan is covering a potential ball into the Norwegian is no longer anywhere near Gabriel (out of shot), who is making the pitch as big as possible.

Meanwhile, Trossard is pulling to the right, taking his defender with him, and Zinchenko drives forward into the ‘left eight’ space, pinning his opposite number. Saliba finally released the ball to Gabriel in acres, he had a wide open angle to play the ball down the line to Gabriel Martinelli, and Arsenal created an artificial counter-attack in an all too familiar shape — the 2-3-5 — but the players in an unfamiliar arrangement.

That Trossard drift from ‘left eight’ to ‘right eight’ was a consistent delight against Wolves whenever Arsenal and Ødegaard attracted the press. Look here how — with Rice and the centre-backs stretching the pitch — Trossard shuffles over to the right, then checks back, then moves to the right again to open space for a dropping Gabriel Jesus.

This level of fluidity feels like a real addition to the Arsenal game and — as long as it’s done at the right times (at Luton in the first half there was too much drifting in our third and it felt muddled) — it could be the key to unlocking some of the more stubborn defences we come up against.

As an Arsenal fan, it’s fun to look at the pitch and not see the exact same patterns as before.

As an opposition player it must be a real headache.

And those rotations are common between Rice and Ødegaard too, with the more advanced player often attracting attention by dropping and allowing the deeper player in that moment to drive forward into the space that is created unmarked.

Here, with Ødegaard deeper, his usual marker is attracted to Tomiyasu on the ball and the Arsenal captain can arrive in the space that opens to receive the ball from Saka.

Or, conversely, Ødegaard coming closer to defenders in possession can pull midfielders out of the block and open alternative passing lanes.

In doing this, Arsenal are starting to create huge gaps between the opposition midfield and their defence. After weeks of relatively stale control at times, these spaces are where Arsenal are injecting thrust into their play in possession.

Oh and the best part? The fun bit? We all want goals and assists and final third action. And Ødegaard looks like he can play deeper than ever yet provide as much output as ever, all at the same time. I didn’t bring Di Stéfano — the ultimate controlling, positionless, output monster total footballer — into this for no reason.

Ødegaard scored a trademark goal from a cutback against Wolves, all actually stemming from his own run forward that helped provide Bukayo Saka with some space rather than being quickly doubled up.

This run off the back of his marker pins Toti, Wolves’ left-sided centre-back, and then continues to pin him as Gabriel Martinelli arrives in space unmarked.

Saka didn’t look for Martinelli, the ball went over to the left as he overhit his cross and in the end we get a delightful trademark finish from the Ø Zone.

And then there’s the final ball stuff. I think many have been disappointed by Ødegaard’s final third output and particularly his creativity so far this season. Against Wolves he was aggressively looking to find runners in behind and doing so with the sort of technical brilliance — using all parts of his foot and all sorts of angles and playing balls impossibly quickly to unsettle defenders — few players possess

Seriously, it is ridiculous the amount of influence he had in the final third and he was unlucky not to grab assists for both Leandro Trossard and Eddie Nketiah.

Arsenal were playing quicker, helped by their more fluid build up unsettling the opposition, and their captain took the opportunity to just be more ambitious.

It was real, ‘playmaker looking for final pass’ stuff. And who doesn’t love that?

As the season goes on, I suspect we’ll see more play like this from Ødegaard but the difference to last season — even though it’s only been a few games where he has really done this — is already stark and showing up in the seasonal heat map when you look at areas just a bit to the left in our own third and right in front of our box.

And I’ve written all this without talking about the perfection of that final half an hour against Luton, which was just an absolute “fuck you, I’m not letting us drop points here” style performance from the man Arsenal tend to look to most when things get tricky. Sometimes a player just decides they will not let their team walk off the pitch disappointed and that’s exactly what the captain did in midweek.

Arsenal’s creative, box-crashing genius is becoming a deep-lying playmaker who collects the ball in his own box to create counter attacks from phases of possession without losing any of his final third creativity or his goal threat.

A deep-lying, goalscoring, box-to-box number 10. You cannot ask for anything more than that.

Brilliant piece, loved it. Thank you.

Fabulous analysis. I was hoping that last 30 against Luton would feature, he just grew and grew in stature, pushing till the last kick of the game, demanding the ball from Zinchenko, and curling the only viable option right onto the forehead of the Rice-Man. Goodnight Hatters. Thanks for a great game, but not today.